I was due there for a four-day meeting and training course, part of the EU Erasmus Plus-funded Enginite project, with partners from Cyprus and Greece. I didn’t have time for the surface journey. In this case I felt the cross-border collaboration benefits outweighed the environmental cost of flying, so I jumped on a plane. But having flown that far, I was determined to have an overland adventure when I got there. I got my chance on the last day.

I was weighing up a visit to the ancient palace of Knossos or a walk down the Samaria gorge, Europe’s deepest. The ravine excited me but it involved an early start and a several-kilometre exposed walk through the sun at the southern end; however, the payoff for the walk would be a boat ride along the coast to the pick-up point for the coach home. Knossos is apparently a site not be missed, but I realised it was the boat part of the ravine expedition that excited me the most.

The answer came the night before when one of our hosts showed me a postcard of Lutero, a settlement that is no more than a collection of small buildings surrounding a turquoise-watered cove, only accessible by boat. She confided that the thing to do was to take a bus in the morning from Chania across the steep central mountains to Chora Sfakion on the south coast, and then take the coastal ferry one stop to Lutero. That settled it.

The following morning I got waylaid finishing up some work – when I looked up the bus timetable I discovered I only had 30 minutes to pack, find the bus station and get a ticket. I jumped into a taxi midstream, bit my nails as it inched forward, ejected myself once more midstream, cut through the traffic and got onboard the only coach heading south with a minute to spare.

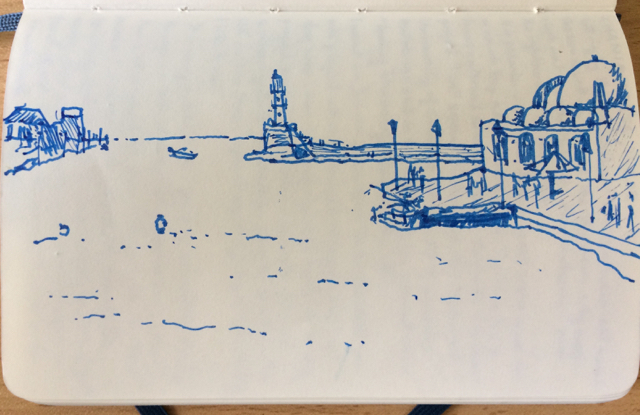

Chania is on the north coast of Crete. Its main attraction is a beautiful harbour built by Venetian contractors. The picture is a sketch drawn one evening of the lighthouse and the sea wall, drawn from a bench on the landward side of the harbour. The second sketch looks back from the harbour wall at the old town with the White Mountains rising steeply behind. It was across these mountains that my coach was now climbing along a twisting and turning oleander-lined highway.

We arrived high above the south coast and spent 40 minutes zigzagging through the slalom course of switchbacks that brings the road dramatically down to sea level. On this side of the mountains the oleanders are replaced with bulbous purple cauliflower-like heathers – there’s beehives staked up and down the hills. At Chora Sfakion, the coach connects with the ferry, which was steaming into port as we arrived, floating on crystal clear waters, its shadow clearly snaking its way along the sea bed.

The coast line here is dramatic. Steep hills crash dramatically down into the sea. Deep clefts have been pounded out of the rock face. Occasionally there is a beach; most of the time though it’s a violent transition from rock to water. After twenty minutes Lutero glides into view, just like the post card: an amphitheatre of small hotel buildings and a pebble beach giving embrace to a lagoon the colour of oxidised copper rooftops. The water is so clear that the small boats tied up on the jetty look like they are floating in mid-air.

I buy a can of beer, a packet of crisps and squatting rights on a sun lounger by the shore in exchange for a few coins. I read my book, go for swims, and consider myself very lucky.

I have been trying to figure out what it is that I find so attractive about boat travel. I’m not particularly excited by cross-channel ferries, which feel more like shopping-centres-at-sea than any form of transport – it’s these smaller-scale itineraries that float my boat. I think there’s a few things at play here. There is the novelty of being on or around water which for a landlubber like me is considerable. There is also a quality of jeopardy: the ferryboat propels us across the impassible waters, but miss it and we are stranded – its strict timetable is a lifeline to be respected. And there is the way their plate steel walls shudder inexplicably and shake us in their innards. It’s visceral.

Ferries are one of our most ancient forms of public transport but unfortunately civil engineers have had it in for them for centuries. Perhaps what is so attractive is that those that remain must either be on seldom-travelled routes that are not worth bridging, or on wild routes that would be a bridge too far. Either itinerary is a sign of a good journey.

As the afternoon slips by I’m aware of my own strict timetable. The six o’clock boat is my last chance to connect with a bus back across the mountains. I move myself closer to the dock, watching the comings and goings on the jetty, hearing the cheers from the bar when Russia scored its first goal of the World Cup. Eventually my return ride appears around the headland and drops its front lip on the pier. As the bars and restaurants disgorge onto the wharf it appears I’m not the only one who couldn’t afford to miss this boat back

Leave a Reply