This week I have had the feeling that I have been struggling recently to find focus on my creative work. I have lots of projects on at the moment, and I am not satisfied that I am being able to draw a cohesive thread between them. I think this is important because I subscribe to the idea that to have impact on your work, you need to be regularly adding to it in a disciplined way – always adding momentum to the fly-wheel, as Jim Collins puts it.

On Friday evening, I went with M to the Olafur Eliasson exhibition, In Real Life, at the Tate Modern. For me this exhibition was much an expose of his way of working as of his artworks themselves, and this exposure to the former I feel has given me the creative catalyst that I needed.

The following are notes and reflections I have made while starting to read the exhibition catalogue.

Creating the home Kalideascope

A regular theme in my training is the creating a physical Kalideascope: a real-life collage of ideas, inspirations, inputs and questions. The final room of the exhibition contains just such a collage, a wall covered with words, references, visual stimuli. These are organised around alphabetically distributed keywords. I am full of creative ideas for projects, some on the go, some not yet started, some have been hanging around for a long time. I now want to make sure I get these pinned up, for record, to help me see connections between those, and so that I can share these idea with M and other people. We are lucky, at home we have lots of wall space. We realise the biggest barrier to creating such wall-mounted displays is not having any paper to print on. Creative action number one: get some paper!

A greater desire for bodily experience

This from the exhibition programme:

‘As daily work is increasingly spent in front of computer screens, and as physical activities are displaced by digital programmes, so there is a greater desire for bodily experiences of the kind provided by immersive installations. And as social life is more and more mediated through technology, the opportunity to come together in a space to enjoy an unusual experience with other people becomes rarer and more appealing.’

Godfery, M. (2019). Olafur Eliasson In Real Life. Tate Publishing.

I find this statement resonates with my interest in several project areas: in getting more involved as a Trustee at Hazel Hill Wood, and what that offers as a place for encounter and for learning; the experience-led learning projects I have done in the past, especially at Think Up and my more recent thoughts about how training could be a more immersive experience; the idea of creating a more physically immersive training about creativity – not just theories on the wall; the analogue skills project, which is intended to be a rediscovery of less mediated, more immersive life experience; playing with physical space through clowning and physical theatre; and dancing.

This exploration and playing with bodily experiences feels like a thread I can see running through my work, which I can draw upon, which I can use to tie things together.

Creating unfamiliar spaces

Eliasson creates unfamiliar spaces using folder geometries and/or mirrors. ‘In this uncertainty these was not just a possibility of a more playful response to your situation but the opportunity to enter into a less familiar relationship with those around you as they also try to navigate these curios spaces.’

The exhibit where M and I spent the longest time was a room with a mirror on the ceiling. Lying on the floor, along with a dozen other participants, my experience was to see my relationship to others in a completely different way. I had a sense that the problems that had pre-occupied for most of the afternoon, a matter of how to set up a payment system for a training course, seemed very small, and located only in my head, now a tiny fraction of all that appears in my field of vision. What’s more, my relationship to other people, and what they are doing, becomes much more interesting than what is in my own head.

This experience leads again to thoughts about how to create training and learning spaces that use mirrors to reinforce our connectedness to one-another.

It’s interesting that this connectedness here is created by an external physical stimulus. The main ways I have been thinking about this connectedness recently have been through ‘tuning in’ to others, say in a woodland context, and through movement and eye-contact, in a clowning context. Eliasson’s work reminds me of the importance of the physical space – the set.

Four principles in Eliasson’s work and associated thoughts

1 – ‘Become aware of the process of perception’ – increased awareness of how you feel in a space, how you occupy it – this increased awareness could lead participants to change their view of how they encounter the world around them and the people in it.

Reading this principle brings to mind my birthday this year when we walked for a few hundred metres or so barefoot through a forest clearing just outside Bristol. Walking bare-foot where I live is a very unusual thing to do. To walk across the town barefoot would, I’m sure, change the way I see the city around me – seeing with my feet.

Why am I interested in looking for different perspectives? Why is alternative perception important? Selfishly, I’m really conscious of my own senses becoming dulled. What I notice about the world being filtered by the familiar.

Changing perception is also important for creative thought – it’s different perceptions that create an alternative framework for creative thinking, that filter what is and isn’t possible.

Changing perception might be important for freedom too. Without the ability to shift perception, we might not be able to shake off the spectacle that might on the one-hand entrance us, but on the other be oppressing us.

2 – ‘Viewer as co-producer’ – ‘In line with psychological and scientific studies into how experience is transformed into meaning, the artist argued that you brought your body to the work, your eyesight, your own sense of small and so on, but also your cultural associations.’

This evokes two concepts that I have been fascinated by for some time: the concept of embodied cognition and the concept of the creative system (which posits that cultural association is a core element in the system of how people develop and propagate ideas).

There is also an association here with problem-based learning: students as coproducer of their learning.

3 – ‘developing a sense of ‘we-ness’’.

4 – ‘Feelings are facts’ – he aims to release powerful feelings in participants. ‘They could be harnessed in the cause of social, economic and environmental attentiveness and responsibility. Feelings could lead to action – and indeed this was the very reason to make art’.

This fourth principle reminds me of another idea that I have recently started to get across in my training – what things feel like rather than what they actually are.

I think engineers are trained to reduce things to a series of measurable and comparable components. The value is in comparability and categorisation, but I think a sense of feeling is lost. I regularly ask trainees how big a room is, and they say, oh, maybe five-metres wide, and I say no, it’s this wide, and I walk across it. This is how wide it is to me. Five-metres is an abstract representation.

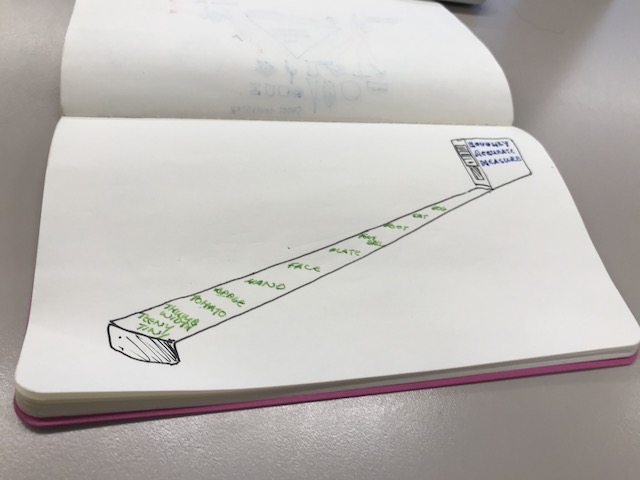

Musing on this theme I just came up with the concept of the feelings tape measure, which seeks to loosen the grip of measurement on our perception. See sketch.

Lots for me to digest here. I’ll start by putting it on the wall.

Leave a Reply