One day I hope this article will be printed in a book. But until then I can be fairly sure that you will be reading it on a screen. In 2021, that is most likely to be a phone, a tablet or a desktop, or possibly some sort of wearable device. In the future, that list could include countless other devices: a web table, a car dashboard, smart glasses, digital wall paper – even a hologram? Such is the speed of technological development that it is only natural to assume that whatever device we have now it will be renewed and upgraded to the next thing at some point. But what if that weren’t true?

Material demand

We know that the demand for electronic devices and their batteries is placing an insatiable demand on the rare earth elements that go inside. The demand for example for cobalt for electric vehicle batteries has made it feasible for mining companies to propose potentially devastating deep-sea mining for cobalt nodules on the seabed. Elsewhere, our electronic supply chains often rely on materials from conflict zones or authoritarian regimes.

Ethical arguments aside, simple lack of supply, coupled with the intensive energy demand of manufacture, mean we will reach a point at which supply can’t mean demand. As climate breakdown disrupts global supply chains, the cost of manufacture is also likely to go up. As economies in the west still seem to be adopting to a react-to rather than prepare-for stance towards climate breakdown, it is likely that these disruptions are going to be felt as shocks to supply rather than gradual transitions.

I foresee that our attitude to tech is going to change radically. Even despite the relative inequalities in digital access, I believe we live in a golden era of digital connectivity and technology. Data and devices are cheaply available. And that availability conditions behaviours. We don’t really need to care how much data we need to save because cloud storage is cheap and ubiquitous. We don’t really need to worry that increased functionality of apps uses up more processing power because the next upgrade of our phone will be more powerful.

But what if increased cost of components meant you weren’t going to get your next phone for a few years. What if cost of batteries actually started increasing? All of a sudden those energy-hungry apps don’t look so appetising.

Growth mindset

There is no reason I can see why the technology that I have in front of my shouldn’t last at least another ten years. Part of the reason why it doesn’t is the well-known concept of built-in obsolescence, the policy of manufacturers to deliberately render technology obsolete after a certain period of time to encourage your next purchase. But I think equally powerful on the consumer side is what I think of as a data and functionality ‘growth-mindset’. We assume we can save everything, so we need ever-more storage. We accumulate more and more apps using up our processing power and so we need faster and faster phones.

I referred recently to the research directly linking increasing road capacity with increasing traffic. I think the same applies to our tech appetite. By increasing storage capacity, we store more until it is full and need more memory. By increasing processing power, we power more apps until we need a more powerful phone.

Reducing lanes reduces traffic

That same transport research also showed that when capacity in the road system is reduced, so too does demand – as has been shown in San Francisco, the heart of the world tech capital. And what’s more, it creates space for a better quality of life in the city. It is not a zero-sum game.

Similarly, I see no reason why we can’t achieve good technological outcomes by actually reducing digital capacity: limiting processing power and storage to actually reduce our demand.It seems that some downward pressure is going to come on our access to tech in future. What if we were start preparing for it now. We could start by asking, what if the device you are using is the last of its kind?

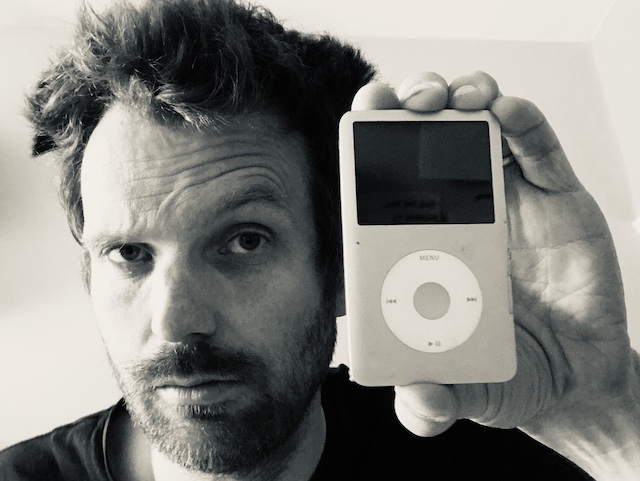

What if this was your last screen?

Not the last one in the world, but the last one you would be able to use. You had to look after it. Keep it functioning. Pass it on to the next generation. How would that change your relationship to it – how you used it and took care of it?

Memory

I think the first inconvenience you would feel – ‘edge’ as I think of them – is your device running out of storage. If we are are assuming this is your last device of this kind, I think it is fair to assume the factors limiting your access to a new device might also limit availability to external storage. So you would have to start thinking about what you keep and don’t want to keep.

Having met this edge before, I know that the first thing to do is look for the massive data bergs, I think of as analogous to the fat-bergs that clog up sewers. These might be routines that are storing up files for you without even noticing. Subscriptions to unlistened-to podcasts that are stacking up. That giant video file you downloaded. Really big programmes or apps that you don’t use very often.

These are the easy wins. These moves will clear some space but inevitably the big gaps will become filled with lots of much smaller items, predominantly images and attachments. Here we need to start thinking about what we really need. Are we really going to print all those images on a billboard at print-quality, or would a smaller file-size do? And then do you really want the photo? And further still, is storing the image on your phone the best place, or for really precious images, wouldn’t it be better to print them out?

The exercise quickly becomes philosophical and existential. What is worth keeping? For whom and how? When should I keep things until? When can I get let go.

In all likelihood, the capacity of your current device is sufficient for you to keep access to really high-resolution copies of your best photos and videos, which will be a delight to keep to hand and show someone. You just can’t keep everything any more.

Processing

Beyond the challenges of memory, the next edge you are likely to reach is that of processing power. There are two factors at play here. One is the invention of apps that use more power. The second is the creation of more and more processing power-demanding operating systems to support these more advanced apps. The former is easier to avoid if you don’t want this increased functionality; the second is harder to avoid. With an operating system upgrade even simple apps work slower on a device which is reaching the end of its manufacturer-recommended (read digitally-obsellesent) service life.

I think the habit here is of being aware of whether the processes you are using are processing hungry or not, and to start steering your choices towards less processing-rich apps. As you move from text, to image, to moving image to moving image, to video conferencing, to video concerning with virtual backgrounds and virtual moustaches (who knew?), so the processing power goes up.

As we reach the limits of our device’s processing power, we might rediscover how to do things with simper means. And limitations, of course, can be the creative stimulus for new ways of doing things. The short-link, for example, an invention in response to Twitter’s character limit.

I still really value the functionality of the iPhone 1, the ability to surf the web, take photos, listen to some music, listen to podcasts, send messages and, of course, make a call. As we no-longer take processing power for granted, we might re-value some of these simpler elements of functionality.

Security

At some point you will run into the issue of security. The case often cited for keeping up-to-date with software upgrades (and my main motivation) is web security. But better online defence against hacking doesn’t necessarily have to mean more processing power, it just ought to mean the tech companies sending new security fixes when they arrive. Again, in the medium term, we may arrive at a worse-off position, in this case that our devices are less secure. But in the long-term, if there are enough people maintaining older tech, then there will be a market for security for these devices. (I am also reminded of the advice of an online security expert friend of mine who says the safest place to keep a piece of information is on a scrap of paper tucked away somewhere)

Connectivity

Consumer device technology advances in step with the wider network architecture that allows us to connect with other devices. If you decide to no-longer upgrade your tech, then it is likely that unless the wider network architecture stops demanding more and more advanced tech, you will fall behind and no-longer be able to connect to wider networks.

It seems that in the medium run, less connectivity will be a consequence of less up-to-date tech, but in the longer run, I see the resurgence of parallel communication networks that user simpler tech. After all, the older tech still works, but what a communication network needs is people who want to use it.

Battery

This part of the jigsaw seems the hardest to figure out. Battery life is usually assumed to be less than device life. It seems a particular tight bind to put yourself into to imagine that you will not be able to get a new battery for your device. But given the supply chain issues I started this post with, it seems prudent to plan for at least limited access to new batteries.

Being able to replace the battery less often would require us to be more aware of battery health. What is the best way to charge and discharge the battery in order to prolong batter life?

Conclusions

To imagine this as our last device requires us to both really question what we use our devices for, and for us to rediscover ways to manage without. From the sunny uplands of digital abundance, it is hard to imagine living without an endless stream of new devices, but many signs are pointing towards a less digitally abundant future.

But we have lived well with less tech functionality. With preparation, imagination and engineering creativity on the part of users, programmers and manufactures, we can learn to do it again – and hopefully even do it better.

What is the Analogue Skills project?

The Analogue Skills Project is my attempt to gather together and keep safe less digital ways of doing things in case we need them again. My aim is to discover/redicover ways of being, feeling and acting that might serve us better.

Read more about the project here and check out my latest posts:

Leave a Reply