It’s hard to know where to start. So much has changed in the last fortnight and there is so much that I feel compelled to write about. But now that our house has also become a remote workplace, a homeschool and playground and locus for all entertainment and time-passing activities, it is hard to find the time to write in an ordered way, so I will capture things as they emerge and look to see the patterns over time. I hope you will bear with me, reader. On my mind today:

- The shrinking horizon of existance

- Surveillance capitalism and Analogue Skills

- Everyone is the same distance away

- Mourning friction

- A great slowing

Shrinking horizon of existence

I have a distinct childhood memory of sitting in my great-grandfather’s garden on the top of a hill in the south of France, looking out over the valley below and wandering, what if, by some terrible catastrophe, we were cut off from the rest of the world, and all that remained accessible for was the valley below? All the people in sight would have to co-operate to find food and water. How would peace be maintained in those early days of realisation and coming to terms with what had happened? And then, how would we adjust to life with a much smaller horizon? As I reckon with not going beyond the limits of my home for two weeks, its appropriate that I should be re-visited by this childhood memory.

Surveillance capitalism and Analogue Skills

I am reading ‘Surveilance Capitalism’ by Shoshana Zuboff. There is so much to reflect and act on here. She sets out a compelling and detailed description of this new form of capitalism that uses our behaviour, activities, personality, even our physiology as raw material for a machine that generates prediction products that are so valuable and pervasive that we are almost powerless to stop it.

I’ve long had an uneasy but accepting attitude towards data privacy. I know that web companies scan my emails to send me targetted ads. I don’t really like it, but I like the free emails, and I ignore the ads. What I realise from reading Zuboff is that the game at play here is much more sinister. Just as industrial capitalists are on an unstoppable mission to extract raw materials from the earth to support growth in shareholder value, surveillance capitalists are on an unstoppable mission to extract more personal data from us to feed their growth. To do that they will push us towards dependency on more and more benign-sounding, convenient technology in order to extract more information – mobile phones, streaming services, satnavs, wearables, home assistants, smart TVs, driverless cars, eyewear. Once hooked, we our behaviour is then more easily modified for commercial gain. And over time, we forget how we acted without the technology, and lose the ability to resist it.

Working from home, socialising from home, shopping from home – all these new behaviours require me to become more and more dependent on tech services almost all of which are feeding in some way the surveillance capitalist machine; all of which are growing our dependency.

It feels more than ever it is time for me to re-invigorate my Analogue Skills project, which aims to help people (re)discover and (re)value non-digital ways of doing things before we forget how.

Everyone is the same distance away

I have a strange realisation that friends, not matter where they are in the world, are likely to be at home, unless they are working in a frontline service. I could call them on a landline, if they still had one, and they would actually pick up.

As my London friend who lives far from her parents in the USA says, now everyone’s parents are just as far away. And indeed so are friends. Geographical distance is no-longer a sorting factor in the selection of which friends a speak with. On the one hand that’s exciting. On the other, I actually find it a bit disorientating.

For me it’s an example of the way things online are frictionless. There is no limit to who I can contact other than my time. To use Matthew Crawford’s term, I have limitless ‘affordances’. But I think we need friction to create some limitations, to help us find our bearings. Having to do work can also make us value more what we are working for.

Mourning friction

It’s interesting to see which industries and jobs have been affected by Covid-19 and which haven’t. Picking up this term ‘friction’ again from my point above, it’s the frictionless work that seems to carry on and the work that requires friction , say by human contact or human action, that is threatened. Tech companies such as Amazon want a more frictionless existance for their consumers to minimise any barriers on the journey from desire to ‘fulfilment’.

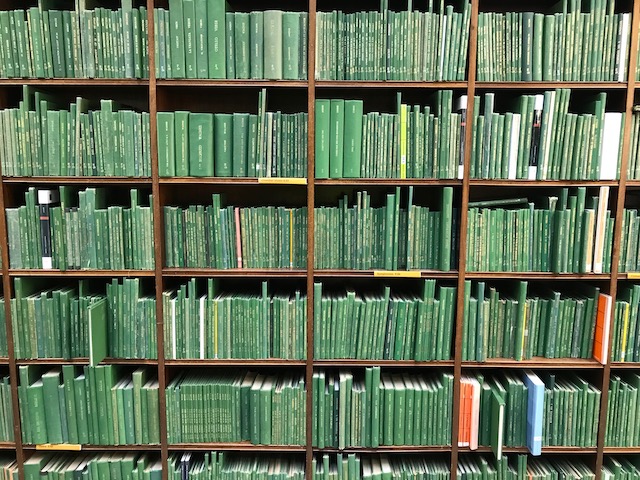

An example of a service that requires friction is a local library. While the libraries have closed, some will have found alternative ways of accessing library services. But it would be all to easy for the physical services not to return once the epidemic has passed and that would be a huge loss.

A great slowing

I’ve mused in recent years about writing more letters. Of course I don’t because I want an answer quicker than a letter can offer. But now that I am likely to be in for three months, what’s the hurry? No one else is in a hurry. My initial instinct in this crisis is to transfer everything online, but we don’t need an instantaneous response. This crisis may be an opportunity to slow the frenetic pace of life.

Mary Stevens

Well done for taking the time to write this. This blog post (from Shift design) is another way of thinking about the digital-human divide – might just provide some food for thought.

https://shiftdesign.org/joining-dots-digital-technology-isnt-enemy-warmth-within-services/