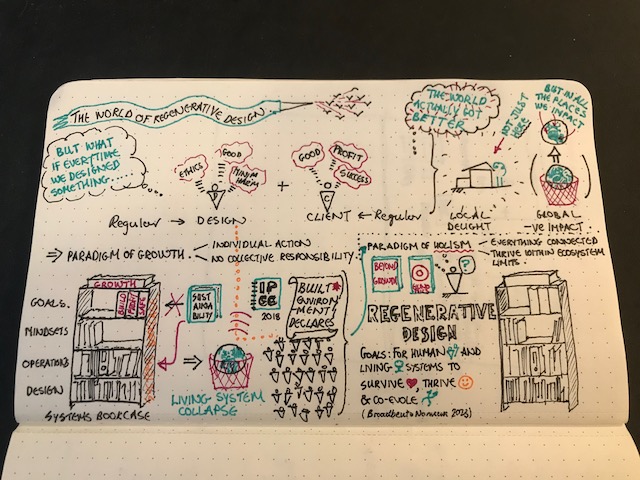

It is a simple question. What if every time we built something the world got better? Not just in the places we construct but in all the places affected by our construction activities. If we could meet this apparently simple ask, then we would shift the construction industry from a paradigm of extraction and damage to a paradigm of healing and repair.

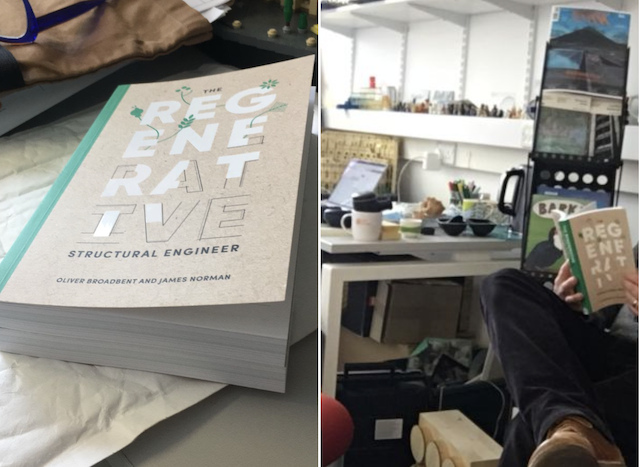

In our groundbreaking new book, James Norman and I explore what it would take for the construction industry to make this shift and what role structural engineers have to play in this transition. In short, what it would mean to be a regenerative structural engineer?

The limitations to sustainability

The starting point for our argument is that sustainability is not working. Quoting Micheal Pawlyn’s review, “they make a thought-provoking and, as far as I’m aware, original observation, that sustainability never developed to a level that would merit the term ‘paradigm’ in Meadows’ terminology. It operated wholly within an economic paradigm of endless growth and this goes a long way towards explaining why it has not had the truly transformative effect that we require if we are to address the planetary emergency.”

In the construction we are starting to realise that we need a different approach if we are to shift from an industry that does net harm to an industry that does net good. That approach, as encapsulated in concepts like donut economics, is holistic thinking. It is the realisation that within our ecosystem’s limits we are all connected and we need to find ways thrive together.

A new approach – regenerative design

It is within this holistic paradigm that regenerative design sits. As we define in the book, the goal of regenerative design is for human and living systems to survive, thrive and co-evolve. Having set out this goal, we define the role of the regenerative designer as creating a transition that enables construction to reach this goal.

The book’s unique contributions

We believe this book brings a number of fresh perspectives and useful tools that can readers understand and apply regenerative thinking in their work.

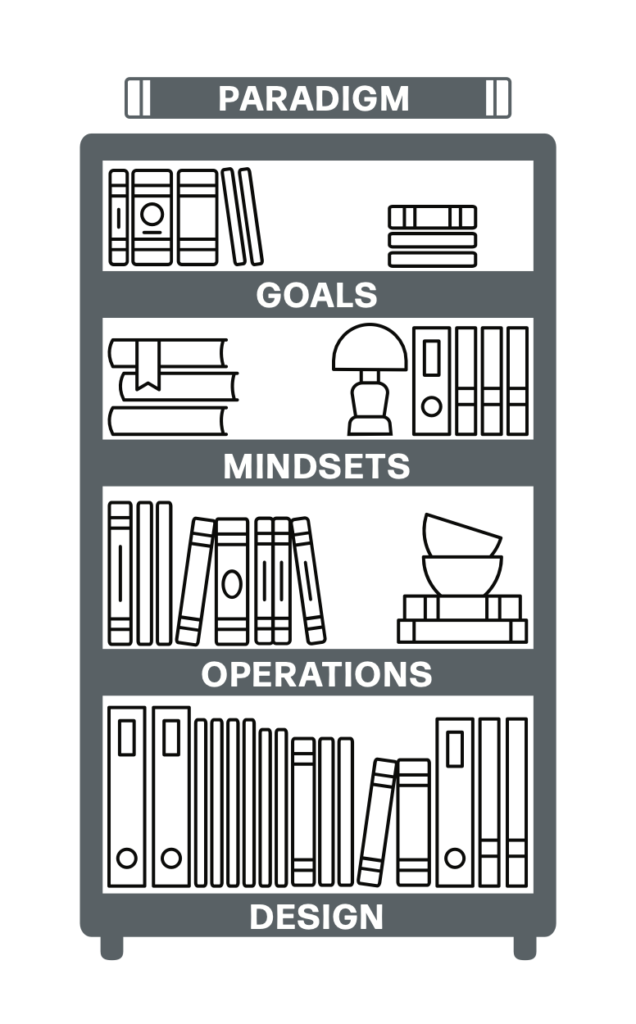

The Systems Bookcase

This model succinctly shows how design decisions are constrained by a series of higher-order system levers, ultimately aligned to our governing paradigm. Through the systems bookcase model we show change can be made at all levels in the system to transition our industry away from net destruction to net thriving.

The Living Systems Blueprint

In creating this transition, we need something to head towards. The best model we have for how to thrive within ecosystem limits is living systems themselves. We identify three characteristics of living systems that can guide us in making design decisions that will help create human and living system thriving. Together, we call these characteristics the Living Systems Blueprint.

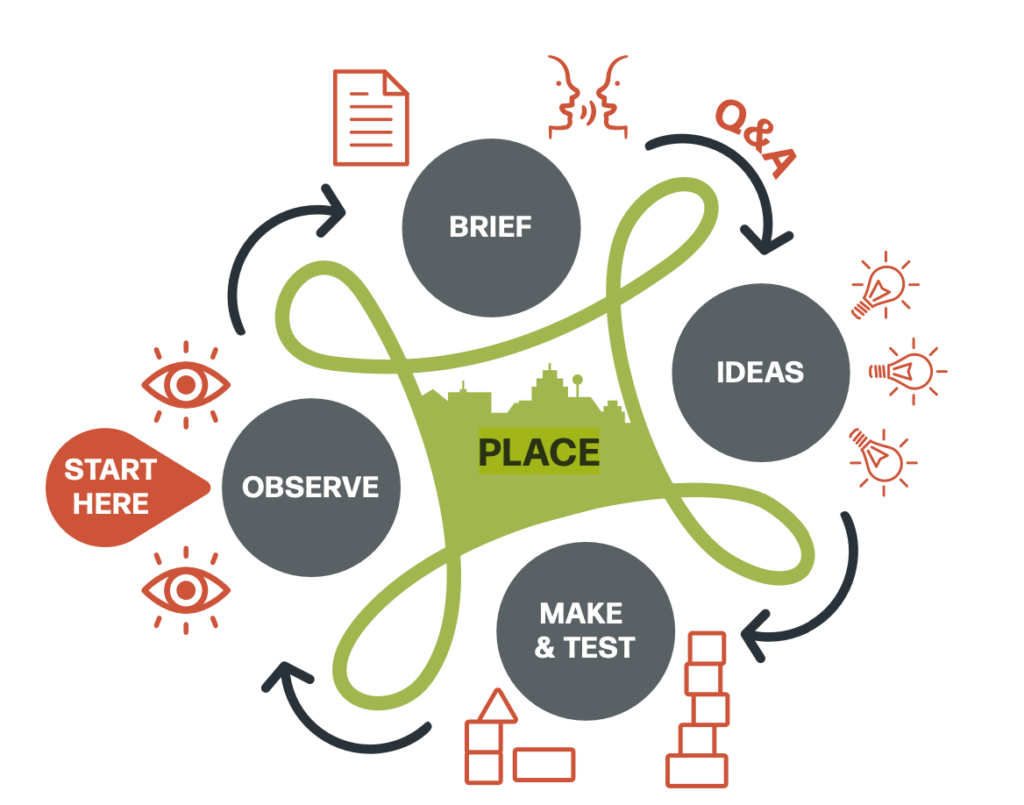

Continuous place-based design

The transition to a construction industry in which we take long-term care for our communities an ecosystems requires us to acknowledge their complexity, and therefore the need for long-term engagement and understanding. We propose ‘continuous place-based design‘ as an alternative to the linear design approaches we traditionally use in construction. By shifting to a continuous approach, we can shift our role from being one of one-off interventions, to one of long-term stewardship of communities and ecosystems.

Challenging the prevailing narratives

Here are some of the key things we would want readers to take away:

Regenerative design is not just trying harder at sustainability

We are advocating for a move beyond the current efforts of sustainability, emphasising that without addressing fundamental systems barriers, construction can’t shift from net destruction to enabling the creation of thriving ecosystems and communities. Regenerative design requires a fundamental shift in approach.

Expanding our notion of the construction site

For the regenerative designer, the definition of the construction site extends far beyond the traditional construction hoardings to include all the places touched by construction, including places of material extraction and the communities involved in the process. This approach goes beyond simple lifecycle assessment of materials, which is generic, and gets into the detail of the places our materials come from. For the regenerative designer, the design work is happening as much at the site of material extraction as at the place of construction.

Don’t call projects regenerative

You can’t point at a project and say that it is regenerative, because within the contexts of the current system, they can’t be. We can look at individual projects and find qualities that show us what a regenerative construction industry could look like. What is regenerative is the work to try and change the system to one in which human and living systems survive, thrive and co-evolve.

Systems-change over scaling-up

We can’t reach regenerative design by simply taking small projects and scaling them up. It is this separate, individualised approach to design that allows the overall industry to be extractive and constructive. Instead we need to look at how we create coordinated system change, for example at the scale of how materials are produced and used in a bioregion, or at the scale of a supply chain. Individual projects have a role to play in experimenting with and demonstrating novel design principles, but change happens when these approaches are coordinated across multiple approaches.

The inherent values of regenerative design

Whereas design is values-neutral, regenerative design comes with an in-built goal: for human and living systems to survive, thrive and co-evolve. The starting point for work as a regenerative designer is to hold and continually maintain in mind a vision for a thriving future. It doesn’t look like the present, it is an act of collective imagination, and we have to do the work to keep this vision alive, otherwise we have nothing to work towards.

Healing is specific and takes time

Whereas our destruction can be indiscriminate, the work of healing is specific and takes time. We have to get into the detail of how our communities and ecosystems are suffering before we can identify how our work in construction can contribute to their healing. So this isn’t about generic attempts to be good, we have to understand what the patient needs, to pay attention, to stay with the work for the long-term.

Practical insights and inspirations

Our book aims to be practical as well as philosophical. The book is packed with examples that illustrate where designers have taken an approach that can help create the transition to a regenerative industry.

While we don’t think it is possible to deliver an entirely regenerative project within the constrains of our current industry, there is plenty that everyone can do to start to create that transition. Chapter 4 is packed with suggestions for how to create the transition to a regenerative industry through the way we design.

Chapter 5 takes the conversation to the level of the rules and regulations that guide us, control us and enable us. Here we encourage readers to find the parts of the system that they have some power over and how to use that power to make change.

And in chapter 6, we take the argument up to the level of mindsets – what are the ways that we need to be thinking in order to hold clearly a vision of a regenerative future and how to bring others on the journey with us.

It’s in our hands

The power to create a transition to a regenerative construction industry is in our hands. We don’t need any new technologies. We just need a clear vision for what we are trying to create, a clear understanding for how the current system locks in destructive behaviours, and tools for creating the transition. Our hope is that in reading this book, structural engineers and other flavours of designer will recognise the power they have and begin to use it to create a transition to a regenerative construction industry. So that one day, every time we build something, the world genuinely gets better.